Woodstock ’99: A Lesson Not Learned

Imagine Fyre Festival, Warped Tour, and DashCon all combined into one event; that’s essentially what happened when they tried to revive Woodstock in 1999.

Netflix’s new docuseries, Trainwreck: Woodstock ‘99, takes an in-depth look at the disastrous concert festival and where things went wrong. How did the festival of peace and love turn into an ill-organized cash grab? Who’s to blame for the chaos that ensued? Most importantly, is this about to happen again?

The Festival

Trainwreck: Woodstock ’99 does an incredible job of exploring the event—from the planning stages to the performances, all the way through the dire aftermath—but if you haven’t gotten a chance to watch it yet, this is the lowdown.

Woodstock ’99 was conceived by Michael Lang, the same man who created the Woodstock brand, along with renown concert promoter John Scher. Just like the original Woodstock, the intent of the event was to promote the idea of community and peace in a time where violence was on the rise in America. Gun violence especially was becoming more prominent on the news, school shootings a more common occurrence. The hope was that Woodstock ’99 would become the same cultural statement as the original and draw attention to a good cause.

As you can probably guess by the documentary’s title, that…didn’t work out so well.

The Docuseries

Trainwreck: Woodstock ’99 is a three episode series with a story that makes the time fly by. It felt like watching a horror movie, which had me sitting on the edge of my seat waiting for the inevitable. I don’t want to spoil too much of the fun, but we’ll give you a teaser taste of the chaos inside.

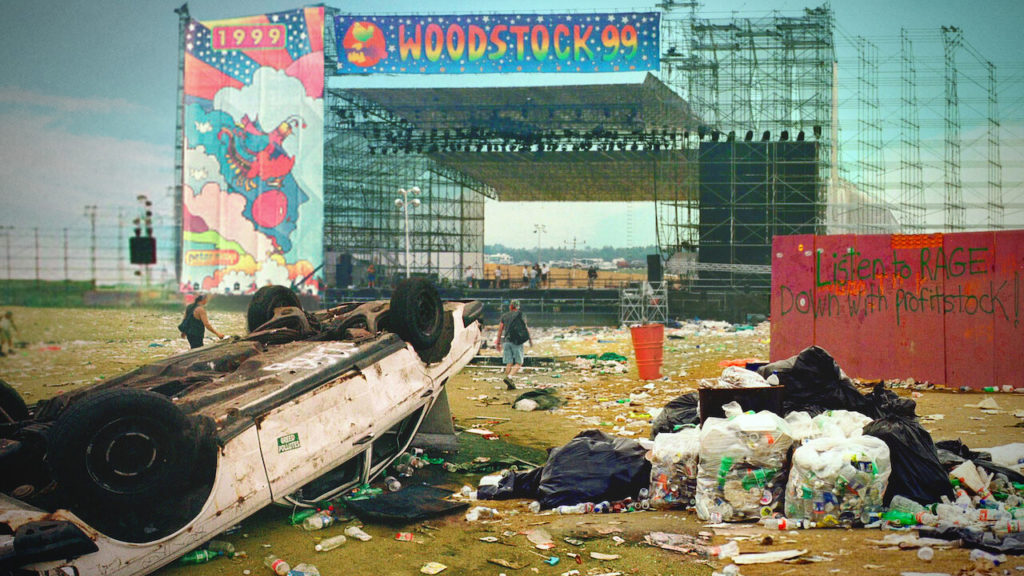

The festival was held on a former airbase in upstate New York, which meant hundreds of thousands of attendees baking on asphalt in a hundred degree heat with little to no shade. Even without the performances and later destruction, the medical tents were flooded with people suffering from dehydration and heatstroke. Concessions were limited, with a bottle of water rising from $4 to $12 over the course of the event. (And remember, that’s 1999 prices. Accounting for inflation, that would be roughly $7 to $21 for one bottle of water.)

Free water was limited and was later discovered to be chemically tainted. The porta-potties were rarely emptied, leading to floods of human excrement on the grounds. And despite all of that, attendees still had enough energy to get so hyped during some music sets that they began physically destroying the sets and sound towers of the performance area—all leading up to a terrifying, fiery finale on the final night.

A word of caution: the documentary can be graphic at times when showing the injuries that people sustained and the conditions they were living in. There is also thorough discussion of harassment and violence against women. Make sure you proceed with caution.

The Blame

After a high-profile catastrophe, there’s always going to be finger-pointing over who’s responsible for the mess. The real answer is that no single party can shoulder the blame for everything; Woodstock ’99 was a perfect storm of mistakes, bad decisions, and corporate greed that turned into a bonfire of hostile energy—but there are certainly some people to blame more than others.

Society

This one is kind of a cop out, but let’s address it anyway. The original Woodstock definitely promoted an anti-establishment worldview, but it was building off a cultural movement of peace and love that already existed. Woodstock ’99 was trying to start that cultural movement in an era that had volatile cultural growth; between the rise of the Internet and technological advancements, things were changing too fast for anyone to breathe. Take a moment of peace, and you’re already falling behind the trends.

The Bands

Celebrity worship is nothing new; we all know just how much influence an influencer can have. Over the course of the weekend, the bands at Woodstock ’99 were encouraged to talk to the crowd and calm them down. To which the bands replied: nah. All you have to do to understand this argument is to look at the recent tragedy at the Travis Scott concert. On the other hand, as one of the interviewees says in Trainwreck: Woodstock ’99, “You can’t blame Limp Bizkit for being Limp Bizkit.” So maybe booking bands with hits like “Get Mad and Break Shit” wasn’t the best move for a festival about peace and love.

The Attendees

Obviously, at the end of the day, we’re all responsible for our own actions; that’s not what we’re getting at. The fact is that doing something for the first time is, in many ways, much easier than recreating something. The people who attended Woodstock went for the advertised environment of peace and love. A disproportionate number of people went to Woodstock ’99 because they knew that—at the original Woodstock—people were drunk, high, crazy, and free. The reputation of the original event attracted a very different demographic, something that wasn’t likely taken into account.

The Producers

Let’s not get it twisted: the bulk of the blame lays at the top of the ladder. The people who signed the checks, booked the bands, and made the final decisions. It’s no surprise that they cut as many corners as possible to make the event profitable, and the concert-goers paid the price. The interviews in Trainwreck: Woodstock ’99 show just how out of touch the promoters were, and the way they coasted through the weekend in complete denial of the chaos. They constantly tried to downplay the damage by saying it was “just a few bad apples,” while refusing to own up to the lack of resources, lack of security, and lack of respect for their customers.

The Future

Event planning is no easy gig. It would be wonderful to say that society has learned its lesson and we don’t need to worry about this kind of disaster happening again—but it’s simply not true. There’s a host of other documentaries about events gone wrong, and there will be more events that go wrong in the future. We’ve got our eye on one event specifically.

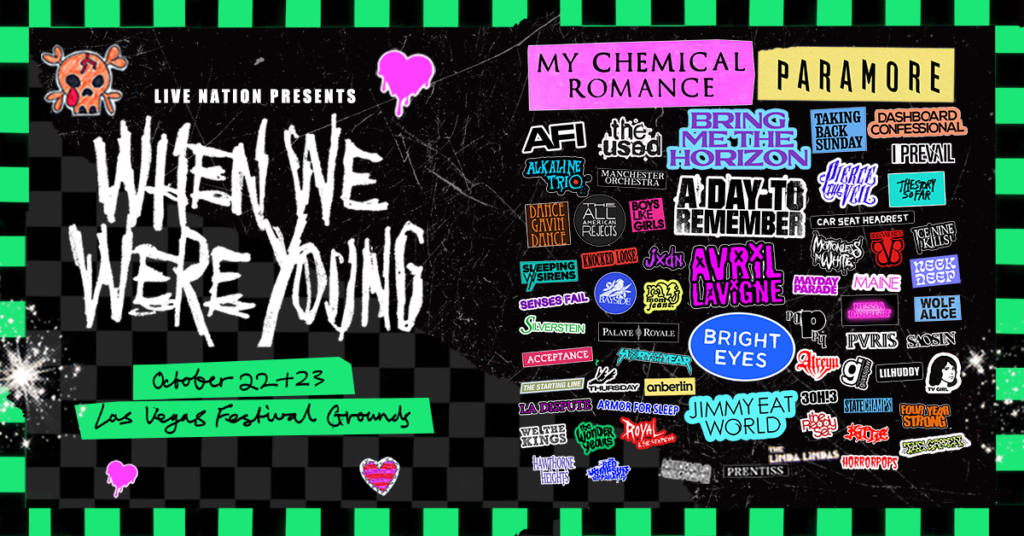

At the beginning of the year, the music world was rocked by the announcement of a brand new event. The When We Were Young Festival came out of nowhere and took social media by storm. With its brightly colored poster chock-full of names like My Chemical Romance, Paramore, Avril Lavigne, Bring Me The Horizon, Taking Back Sunday and more, people were convinced it was just an edit—a dream lineup someone had thrown together in Photoshop. There was no way we were really getting a chance to hop in a time machine and step back into the 2000’s.

People dove head-first into investigating…but there wasn’t a lot to find. The official social pages only had one post announcing the event. The website was bare except for a few graphics and ticket prices. Bands were bombarded with questions from people begging to know whether or not this was legit. Some of the performers didn’t even seem to know they were making an appearance.

Yet, despite the doubts and dozens of red flags, tickets went on sale: general admission for $245, a VIP package for $520. And they sold out fast. Some people were genuine believers. Others didn’t want to risk missing out if there was the slimmest possibility that it was true. TikTok was full of cautionary videos from elder emos, warning people not to blow their money on what would most likely turn out to be a scam. After all, veteran rockers have seen this kind of thing before.

Over the last seven months, the hype has died down, but it appears that the When We Were Young Festival is still a go. If you go to the festival website now, things look a lot more legit. There are additional “side shows” lined up around the country, and on the bottom of the site, a hefty list of companies sponsoring the event. That being said, just because an event is legit doesn’t mean it’s a good idea. We learned that from Woodstock ’99.

Whether it turns out to be a triumphant return or a new docuseries in the making, we’ll be keeping our eyes out come late-October. In the meantime, Trainwreck: Woodstock ’99 is available for streaming on Netflix.

–